On the American Catiline

and Being There

By Polybius Vegas

“What brought him to the election with a gun on his shoulder, and a mob at his heels; and [the villagers wondered] whether he meant to breed a riot in the village?’” Washington Irving — Rip Van Winkle circa 1820[1]

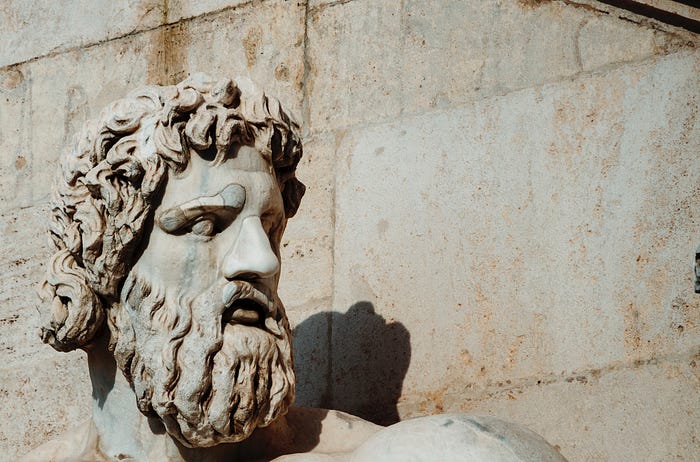

In the early 60s BCE, a Roman patrician named Catiline planned and lead an armed insurrection against the Roman commonwealth. His co-conspirators were a motley crew, a mix of bitter Sullan soldiers (Sulla was a republican general of some regard that had made a name for himself through his successful campaigning in north Africa and his own violent power grab. The soldiers that had served under him were at this time hanging around Rome, often destitute and full of resentment over their lack of war booty and land to retire on), hedonistic aristocrats drowning in debt, his apologists and allies in the Senate, and everyday poor people who had been dispossessed of land (some of this dispossessing had been done by the Sullan soldiers themselves). Cicero, the famous Roman orator, was running for the position of one of two consuls in Rome (the highest office in the Roman republic, like President kind of, but there were two) against Catiline. Cicero was a novus homo or new man, which meant he was the first of his family to come to the big, capital city and try and make it in the Roman political hierarchy. Cicero was not part of the traditional aristocratic families of Rome, and thus by some traditions, he should have been excluded from hold the office of Consul. Cicero, being a public figure that seemingly enjoyed broad and stable support, was tipped off to the plan almost immediately after it was settled. Cicero denounced Catiline to the Senate, in a dramatic speech still translated by Latin students today, and called out Catiline’s supporters in the Senate as traitors to the republic.[2] The conspiracy failed, but Cicero’s response to the conspiracy, to execute the conspirators without trial, has been cited as one of the reasons for the continuation of what was already a very violent political period in the republic. Cicero would eventually lose his own life (and have his head displayed on a pike in the forum) in the violence leading up to the Ides of March and the eventual founding of the empire under Augustus Caesar.

The supporters of Catiline were all aggrieved (whether in actuality or only in their imaginations) and other than the aristocratic playboys that were his closest supporters, many of his supporters had reason to be aggrieved, for they were people that suffered under the Roman system. The Roman republic was not a fair or politically stable space, and redress of wrongs for people of lower social status was often very hard to come by. What tied the supporters of Catiline together was that their motivation for conspiring to end the commonwealth came from the same impetus: personal advancement and gain. They were not interested in the health and well being of all the people under the imperium of the republic, but only their own. In rebellion they had hoped to gain what they had failed to gain with the way they had conducted their own lives: whether they had frittered away a family fortune on partying until they were deeply in debt, were an old soldier who had bet their future on the wrong horse and lost everything, or were everyday people that were oppressed enough by some aspect of the Roman social and political structure that they were already on the verge of rebelling. What all of them had not counted on, however, in the lead up to the insurrection and on the day when their plan was to be unveiled, was the utter stupidity of the plot itself, its leaders, and its supporters in the Senate. This is perhaps the broadest and closest way that the Catilinian conspiracy resembles the Trump insurrection.

One cannot help but see Donald Trump as a pitiful sort of contemporary Rip Van Winkle. A man that instead of sleeping through the last few decades of American life, has instead devoted his life to pretending as if they simply have not happened, deconstructing, eliding, canceling. It seems what he wants to cancel the most is any notion of a proudly diverse America, despite the fact that America has undergone a fundamental demographic shift over this same period. It is Donald Trump himself that is not really real, but his banshee cry can be heard as the birthing pangs of a new America, as she emerges fully formed from his diseased body; gathering herself up resplendent from the rolling Pacific surf. As the poet, Jim Morrison asked: “have you forgotten the lessons of the ancient war?”[3]

Trump is an empty vessel, a creative contrivance of America itself, and nothing else if not that. If he and Rip Van Winkle are similar in that Trump also seems to have no recollection of the past few decades and is completely flabbergasted by the new world that surrounds him, they are dissimilar in that Van Winkle was a simple country man, who actually seemed to be decent enough and enjoyed life, despite forever running away from his “termagent” wife and her tongue. “Rip Van Winkle, however, was one of those happy mortals, of foolish, well-oiled dispositions, who take the world easy, eat white bread or brown, whichever can be got with least thought or trouble, and would rather starve on a penny than work for a pound.”[4] Donald Trump is a man of convenience in so many ways and these ways are not as benign as old Rip’s. He was a drive-thru president. A man who has “written” more books than he has read. He exists in and of television alone, is suckled and maintained by it and is himself a composite construction of some of the great boobs of American television. People seem to assume that the internet has rendered television moot, yet nothing could be further than the truth. Donald Trump is the ultimate personification of the American television “hero”: he has the self-righteous indignation, casual racism and Anglo-Saxon confidence of a lounging Archie Bunker; he has the intellectual capacity and entitlement of a Homer Simpson; he has the conniving love of power, and ferret faced love of sycophants and pageantry of a Frank Burns; the narcissistic self-involvement of a George Costanza; he has the public speaking and interpersonal skills of a Michael Scott and about the same amount of social grace to boot. In M*A*S*H*, whenever the real Colonel, Blake or Potter, is called away from the camp on military business, second in command Frank Burns takes over. On taking command, Frank Burns would inevitably embroil the camp system of function in an enormous mess of petty rulemaking and suspicion, basically making everyone’s life hell. Why did Frank do it? Seemingly just for shits and giggles, but also because he hated the freedom, openness and anti-war attitude of some of his other surgeons, and he wanted to exert his domination over them. He wanted to force them to be like him, which is the very inversion of our ancestral liberty itself. We have just had four years of rule by a Frank Burns.

Jerzy Kosinski’s short and simple novella Being There[5] (1970) best defines the social and cultural processes that culminated in President Trump, the American Catiline. The premise of Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There is simple enough: how would a person educated solely through the watching of television, without ever encountering the “real” world, act and think if this person was suddenly thrust into the world beyond TV? Kosinski’s protagonist, “the gardener”, represents both an active character and a vehicle for philosophical inquiry. The gardener works and lives in a walled estate in Washington DC. The estate belongs to an aging partner at an influential DC law firm. The gardener came to live with and work for the lawyer as a small child, a sort of foundling. He learns the basics of how to maintain the garden in a brief few weeks of training from the old gardener and then he is on his own. He never leaves the estate, he is provided all of his meals by the staff of the house, and meticulously maintains the garden exactly as it had been when he took it over. He lives in a small room at the back of the house, across the hall from the maid’s room. Over the years he gets to know one of the maids reasonably well, his relationship with her is the only true human relationship he has until he leaves the house, and it isn’t all that deep.

The lawyer who owns the estate became sickly and dies. Another lawyer, one of the partners of the Gardener’s lawyer, shows up at the house to execute the will can find no trace of the gardener in any of the pertinent documents. He asks the gardener where he comes from, and he doesn’t know. He asks the gardener if he has any identification or any proof of the claim he is making against the estate, the gardener does not understand him and leaves the room after being given notice to vacate. The gardener, through no fault or consent of his own, becomes a “nonperson”, someone who exists in veridical reality, but lacks even the very basis for a “legitimate” existence. The gardener knows, from television, when lawyers come after a death, their authority is total and that the house will soon be sold. He packs a suitcase and leaves. Wandering Washington DC, he is almost immediately struck and pinned against a wall by a limousine; he has no real conception of traffic or how to conduct himself in public space. He is injured, but the owner of the limousine offers to provide him with free medical care if he forgoes any legal action. As he does not understand any of what is being said to him but understands from television that it is always more advantageous to agree and smile, he agrees to be taken back to the woman’s house so he can rest and be cared for. As it turns out, the woman in the limousine is the wife of one of Washington DC’s most powerful corporate power brokers. He becomes involved in her social circle while staying there, and whenever anyone questions him on his identity, he simply deflects and reverts to talking about the garden.

In the limousine, the woman asks the gardener what his name is, and he says, somewhat tentatively as he is not practiced in conversation, that he is called “the gardener”. The woman transposes this to hear a name: “Chauncey Gardiner”. He agrees that it is his name, and he takes it as his name. When pressed, the only thing Chauncey knows how to talk about is his garden but people always take his basic narrations of the ways of good gardening as a metaphor to mean, well, whatever they want to hear. His years of simple, honest labor have left him uncomplicated mentally, almost meditative, so holistically he presents on television as an accomplished man who is calm and humble. As a whole, Kosinski characterizes him as achingly telegenic and likable, and his puerility is a big part of this, he is a blank slate and does not mind listening, although he never understands what is said.

It is the total lack of substance in Chauncey Gardiner that makes him so attractive in Kosinski’s narrative. His deep familiarity with the norms of television allows Chauncey Gardiner to seem always “in place” and “on point” in real life and on television. This is in spite of the fact that he never quite manages to say anything at all about anything. People can paint him with their imaginations into whatever it is they want their leader to be. Everything Trump says seems to be a (bad) paraphrase of something someone else has said to him, and he repeats the same thing over and over, like the garden metaphor. There is not a single overarching principle or conceptual thought in anything Trump says, except a naïve, simplistic understanding of the world in terms of black and white, with easy answers and lots of diversions. He believes nothing and seemingly thinks next to nothing, he only acts. Gardiner, sure enough, moves ever further into the higher rungs of the DC social and political ladder, and the story ends with him en route to becoming president of the United States. One wonders if that imagined presidency played out along similar lines to the Trump presidency, the tendrils of the destruction of which are still being knotted back together as I write.

Trump recently ran a presidential campaign with no platform at all, yet this, seemingly for many Americans, was a good political platform. TV imbibing contemporary Americans seem to thrive on simple explanatory narratives like Chauncey Gardiner’s garden metaphor and it is the appearance of Gardiner on television that makes him such a saleable, if vapid, public figure. Yet, this vapidity is but a bonus — in both cases. Throughout Being There Kosinski is always careful to narrate scenes of consternation and flummox on the faces of (almost always half of the room) some of the more astute observers of Gardiner’s empty public proclamations and the cult of personality that quickly develops around him. Although these observers remain gaping, no one among them has the power to effectively contradict the narrative of Chauncey Gardiner the media begins to construct about it, a narrative where he is a brilliant economist who is going to save the United States, so they are forced to go along with it. Gardiner begins to make television appearances, shilling out his garden metaphor on many unsuspecting interviewers. The whole story, after Gardiner leaves the estate, and the America he goes into, reverberates with crisis and impending doom. The economy is crashing, riots are taking over cities and nuclear war is ever on the horizon. Chauncey Gardiner’s garden metaphor is taken by many Americans in the story as evidence of the utter truth of, and thus the reason for their belief in, that other American altar, perennial optimism.

There are many Americans whom America does not work for. Hunter S. Thompson used to talk about the “doomed” of America, which I think is an excellent way of conceptualizing the people in America who are now, or who were in the past, outside the streams of wealth and prestige many Americans take for granted, take as a birthright. These Americans have legitimate grievances. This is why someone like Gardiner, like Trump, appeals to many Americans, and the reasons why are easy to pick out, they craft a narrative whereby they pretend to lift up the “doomed” by themselves alone. Catiline did this as well. When the public, inevitably, finds out that these prospective tyrants duped them (as many Capitol siege protestors are now finding out the hard way), and it was not for the benefit of the public that they called for support, but for their own private aims, the reaction is far worse than almost any other condition of betrayal or double-cross. For when one takes legitimate anguish and turns it into scheming political games, while at the same time claiming it is the people you care for, the wound caused is deep and dirty.

We are the land of the television president, and this is the bed we lay in. Television has no thematic chronology, no canon, viewing it is passive, it creates no context, it is completely without historicity: ultimately, it is a reflection of the unrelenting newness of the present moment itself.

When the apologists of insurrection, and those backers of Trump who willingly, before our eyes, destroy the res publica for their own venal ends, forgetting the events of January 6, it is television and the internet that lets them do it. They inhabit a semblance of reality wherein Trump is truly aggrieved, where the election was rigged and where they and their buddies are the only people in the United States who know anything at all. The only problem for them is that this is an imagined reality, and all around them the sacred progress of the eternal present clangs. They squirm to shut it out, but it is there, at the edges. Do you know what that is Senators? It is the voice of your own Unionist ancestors, calling you to do right by the project of their own lives, the United States of America.

I do not, by any means, contend that Trump is exactly like Catiline — there is no exact historical correlate for this moment of present existence — but rather only that the “characters” of Trump and Catiline rhyme, a decent couplet indeed, the two. Catiline was born to wealth and influence, he did not earn it and therefore did not understand the work, violence and power that underpinned his status. This was the concern of his father. Therefore, Catiline may be defined as holding undeserved social status in a system that encouraged, to a significant degree, upward social mobility, like Trump. Let us now turn to Sallust himself for his estimation of the social climate that produced Catiline: “For [now] avarice undermined trust, probity and all other good qualities; instead, it taught me haughtiness, cruelty, to neglect the gods, to regard everything as for sale.”[6]

Trump is an overgrown playboy. As was Catiline. This was what he lived for, and maintaining his lifestyle, and also the pure desire for kingly power, was the motivation behind his ploy for power and the end of the republic. The Catilinian War was not really much of a war but rather a poorly planned oligarchic coup conducted by stupid and spoiled rich brats and their allies. Again, I turn to the words of Sallust himself, “In so great and so corrupt a community Catiline kept himself surrounded (it was very easy to do) by hordes of those responsible for every depravity and deed, like bodyguards. Whoever had ravaged his ancestral property by means of his muscle, stomach or groin; anyone who had run up a huge debt to buy his way out of some depravity of deed; all those anywhere who were convicted in parricide or sacrilege in the courts (or who feared the courts in the light of their deeds); those whose muscle and tongue made provision for them by perjury or by civil bloodshed; all finally who were agitated by depravity, destitution, and conscience — these were Catiline’s nearest and dearest.”[7] The conspirators made almost no attempt to disguise the machinations of their plot, they talked almost openly about it and proceeded stupidly, and naturally were foiled.

Should Trump and his junta of ebeneezers be allowed somehow to succeed, it will guarantee that the United States and its Allies will ‘lose’ the same war they now think they won in 1991. Without rule of law, without the old limits imposed by true Christian ethical moorings, without the contributions of the diverse and productive peoples of the Americas, the United States stands defenseless against those who only believe in the righteousness of brutish force. The time of Catiline was a time of great unrest in the republic, unrest which would eventually lead to the wars of Caesar and Mark Antony and the founding of the empire under Augustus. The great Cicero did not himself to escape the fate of many a politically impudent actor, as he was beheaded in the social turmoil leading up to the end of the republic. The republic resisted Catiline initially, and its institutions held, but just only. Eventually, it fell by the forces that Catiline and others had represented and stoked, and the representative government began to seem untenable if no one would follow the basic rules. So when Augustus set up the empire, it was a relief to return to normalcy and ordinary. So what is it Ted Cruz of Calgary, Canada? What is it Rand Paul? What is it Hawley, who very badly needs to sit down with his Cicero reader and practice his declensions? How best do you sum up your support for this man? Why did you vote to acquit someone so clearly and obviously guilty? Perhaps, I can best sum up why in the words of Julius Caesar at the Senate trials for the Catilinian conspirators:

Many of those who gave their opinions before me expressed their pity for the situation of the commonwealth in a neat and splendid manner […] everywhere [is] filled with arms, corpses, gore and grief. But by the immortal gods, what was the point of such a speech [against the conspirators]? To make [the conspirator’s apologists] hostile to the conspiracy? Naturally a man who has not been stirred by so great and so frightful an act will not be influenced by a speech.[8]

Keep in mind, here, that what the Senate was arguing over then was not whether the conspirators should be punished or not, but whether or not they should be killed immediately without trial for taking up arms against the commonwealth. For a trial of the central institution of governance is not limited by the constraints of other courts, they have ultimately the authority of the government, of the people, and may try who they will, using the evidence that they will. In the case of Catiline, the conspirators were killed without trial, and this hastened the coming end of the republic. What Catiline’s apologists wanted for the conspirators was for them to be locked up in a prison. Let us learn from the past and not over punish, but also let us heed the warning of Cicero in his deliberations over conspirators against the republic: that while to do nothing against an attack on the holiest of holies of governing institutions will buy personal comfort and safety for a brief time, in the end, it can only mean the ultimate demise of the republic. There must be a response. We must also wrest our democracy from the confines of television and television presidents. The combination of the modern Republican(Trump) party, the internet and television have wrought much destruction by a television president. We need to repudiate not just the man himself, by the foundational anti-democratic and nativist principles he and his supporters espouse. We need to get to work.

America, let us rise anew out of history. If we prioritize the local, the human, the ordinary, our democracies will prosper and grow old. If not, then I myself will be forced to off and find old Rip Winkle for a pipe and walk and maybe even some drinking and bowling in the woods. After this, finally, an afternoon nap in the faerie woods, leaving all else to fortune when I wake.

“From the Tao Te Ching, 53:

The Great Way is very smooth

But people like rough trails

The government is divided,

Fields are overgrown,

Granaries are empty,

But the nobles’ clothes are gorgeous,

Their belts show off swords,

And they are glutted with food and drink.

Personal wealth is excessive.

This is called thieves’ endowment,

But it is not Tao.[9]”

[1] Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle: A Posthumous Writing of Diedrich Knickerbocker, 1819–1820.

[2] Sallust, Catiline’s War, The Jurguthine War, Histories, London: Penguin Classics, 2007, translated and with introduction by AJ Woodman, xi-xxxiv, 3–47. Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, entries on Catiline, Cicero and Sulla.

[3] Jim Morrison and the Doors, “An American Prayer,” Electra/Asylum Records, 1978.

[4] Irving, Rip Van Winkle.

[5] Jerzy Kosinski, Being There, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc, 1970.

[6] Sallust, Catiline’s War, 8–9.

[7] Sallust, Catiline’s War, 34.

[8] Sallust, Catiline’s War, 34

[9] Lao-Tzu, Tao Te Ching, translated by Stephen Addiss and Stanley Lombardo, introduction by Burton Watson, Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1993, 53.